Stones from the walls of the Temple Mount are scattered in various locations, including the Knesset, the Kirya in Tel Aviv, the President’s Residence, and the warehouses of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Spring 1995, exactly thirty years ago: The “Alive and Existing” (Chai ViKayam) movement, through its attorney Naftali Wertzberger, petitioned the High Court of Justice against the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The reason: During the development of the area southwest of the Temple Mount—what is now known as the Davidson Center—the Antiquities Authority intended to restore (and eventually did restore) one of the Umayyad palaces from the early Islamic period, the remains of which stand at the foot of the Mount, using stones that originally came from the walls of the Temple Mount built by Herod.

In its defense, the Antiquities Authority claimed it had merely dismantled a wall of an Umayyad palace to expose the Herodian street underneath, and then used its stones to rebuild another Umayyad palace nearby. However, the truth is more complex: the Umayyads themselves, during the construction of their palaces about 1,300 years ago, had already used Herodian Temple Mount stones as building material.

During the destruction wrought by the Romans in 70 CE, they furiously toppled the Mount’s walls and the staircase leading up to it from the southwest—at the point now known as “Robinson’s Arch”—onto the street below. Some of these Temple Mount stones still lie at the foot of the Mount to this day, a testament to the destruction. However, over the past two thousand years, various conquerors repurposed them as building material for their own structures—a practice known in archaeological terms as “secondary use.” The Umayyad rulers, as mentioned, did the same in their time. Incidentally, the Umayyad palaces restored by the Antiquities Authority stood for less than forty years—from around 710 CE until the devastating earthquake of 748.

In the spring of 1995: From the outset, the petitioners achieved a significant initial success when the late Justice Tzvi Tal issued an interim order freezing the Israel Antiquities Authority’s work at the foot of the Temple Mount. He instructed the Authority to respond within thirty days to the question: “Why should it not be prevented from using stones from the Temple, its courtyards, its walls, and its staircases in the project of reconstructing Muslim palaces from the Umayyad period—a project the respondent has begun implementing near the southern wall of the Temple Mount.”

One way or another—and unsurprisingly—the High Court of Justice eventually rejected the petition. “We are satisfied,” wrote Justices Aharon Barak, Dalia Dorner, and Shlomo Levin in a very brief ruling issued in mid-summer 1995, “that in light of the response, there is no basis for our intervention. The dispute between the parties is narrow and concerns the respondents’ decision to transfer stones from the Temple Mount wall found in one Umayyad palace to another Umayyad palace, in order to expose the Herodian street.

We do not believe there is cause to intervene in this decision. We have noted the respondents’ statement that there was and is no intention to take stones from the rubble scattered in the area and use them to reconstruct parts of the Muslim palace.”

In recent months, the petition—almost ancient in itself—has been revived by the “Wall Guardians Association,” which is protesting the placement of a stone from the Western Wall in an exhibition at Ben Gurion Airport.

According to the association, beyond the halachic (Jewish legal) aspect—which, once again, they claim the state institutions have failed to acknowledge—the use of Temple Mount stones violates the Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel, which states in Section 3 that “the Holy Places shall be protected from desecration and any other harm, and from anything that may offend… the feelings of the members of the religions with respect to those places.” They also argue that it constitutes a violation of the Protection of Holy Places Law of 1967, which imposes criminal penalties on anyone who “harms a holy place in any way.” In this context, the association also cites the Antiquities Law, which requires approval from a special ministerial committee before using an antiquity taken from a site designated for religious use.

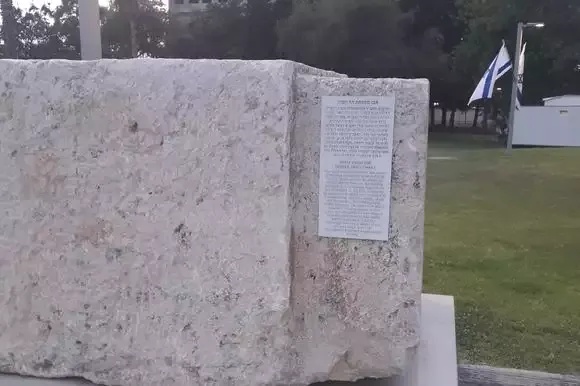

Truthfully, Herodian stones from the Temple Mount are indeed scattered today in various odd and unexpected places, and it sometimes seems as though the State of Israel simply distributes them among its institutions, using them as a means of bestowing prestige and status. Thus, stones from the Temple Mount—of the well-known, heavy Herodian variety—can now be found in the courtyard of the President’s Residence.

There are Temple Mount Stones at the Kirya in Tel Aviv as well.

The stone at the airport was brought there in recent months after spending years at the plaza of the Knesset. Another stone is stored in the Israel Antiquities Authority's warehouses and is occasionally taken out for display. Incidentally, as far back as 1969, during the construction of the President’s Residence, a stone from the Temple Mount was brought to the courtyard. However, President Zalman Shazar later ordered it removed, explaining that he had not even been aware of its presence until he learned of it through the media.

Another stone from the Temple Mount, which originally stood atop its southwestern corner and bears the inscription “to the place of trumpeting to…” was thrown down by the Romans during the destruction and is now, for some reason, on display at the Israel Museum—rather than in its original location.

PHOTOS: Use according to Section 27 A